Modern life hums at a volume that rarely dips. Notifications ping, feeds refresh, and every moment seems to demand documentation. Adults in their thirties and forties, especially those juggling careers and families in Canada’s busy cities, often feel like their calendars are orderly while their minds resemble messy desks.

Many are rejecting a culture that equates constant output with worth.

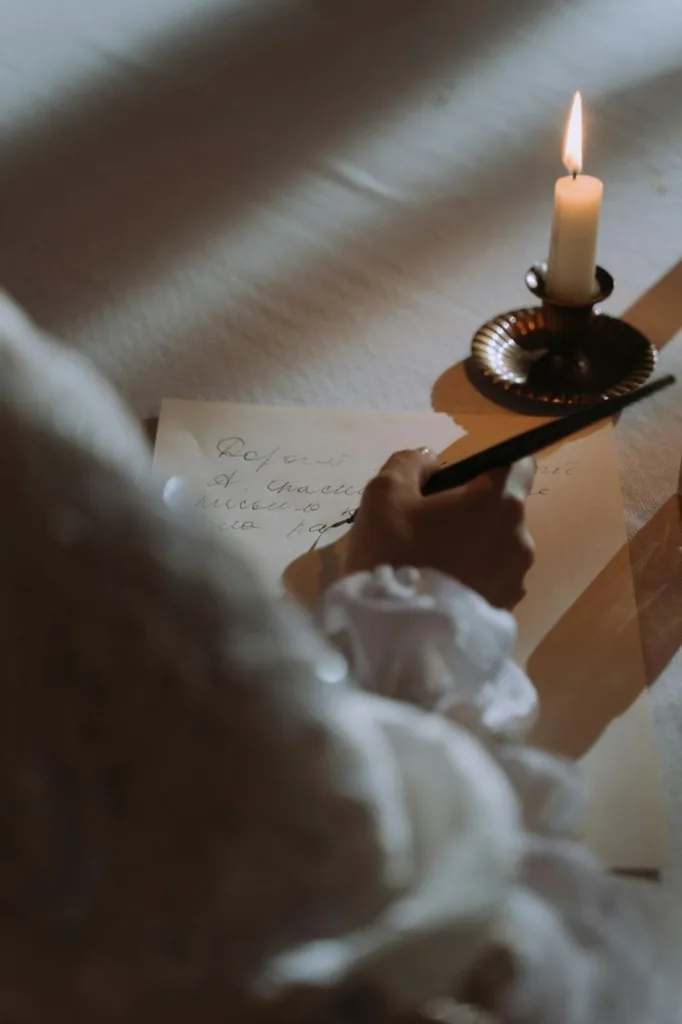

They crave something slower — a way to pay attention without performing. Out of this discontent has emerged a letter writing revival, a re‑embracing of an analogue practice that seems almost subversive in an age of instantaneous messages.

At first glance, sending a handwritten note appears quaint. Look closer and you’ll see a deliberate act of reclaiming time and attention.

This article explores why the letter writing revival resonates with overloaded adults, how it differs from digital communication, and what it offers beyond nostalgia. The aim isn’t to dispense advice or promise transformation. Rather, it’s to illuminate an old habit that speaks to contemporary frustrations and offers a way to connect without feeds, metrics or performance.

What the return actually looks like now

When people say “letter writing is coming back,” they’re not usually talking about some grand Victorian comeback. It looks smaller than that, and more ordinary.

It’s a handwritten card slipped into a birthday gift instead of a quick text. A note left on a counter. A real envelope sent to someone you still like a lot, even if your relationship mostly lives in a chat thread now. And, increasingly, it’s pen pals: people choosing a slower channel on purpose, either with a friend who’s far away or with someone they’ve never met.

That last one matters because it solves a practical problem. Plenty of adults like the idea of writing letters, then stall at the simplest question: to who? A pen pal is someone you exchange letters with regularly, so the habit has a destination. It turns “I should write” into “I’m writing to someone.”

The revival also shows up in the objects people buy and keep. Nice paper. Stamps. Fountain pens, tools that make the act feel real enough to repeat. In a culture where most communication is frictionless, a little friction starts to look like a feature.

Why we stopped and why it’s returning

The act of writing to someone, pen, paper, envelope, stamp, used to be the primary way to sustain relationships across distance. Over the past few decades convenience has edged out ritual.

Texts, emails, and DMs are efficient but often disposable. The epistolary, writing in the form of letters, is one of the oldest forms of personal storytelling, and even advocates of modern communication note that it offers something deeper, slower, and more human than quick messages.

Digital communication tends to prioritize speed. We react and move on; messages are read and forgotten. Over time, we “traded presence for convenience” and largely stopped writing letters.

The cycle of sending and consuming information without pause fosters a constant mental hum. Many adults describe feeling both connected and strangely alone. The pandemic sharpened these feelings by pushing even more of our social lives online. Amid these conditions, the letter writing revival has gained momentum.

People sign up for pen‑pal programs, join local writing clubs, or simply pick up a fountain pen and write to an old friend. Each envelope becomes a small rebellion against the expectation to be always on.

What letter writing offers that digital messages don’t:

Creativity without a “right” method

Letter writing offers a form of creative expression that doesn’t require purchasing art supplies or learning new software. You decide on tone, length and content.

You might include a pressed flower, a photograph, a poem or a doodle. There are no templates telling you how to write the perfect letter. In this way, the letter writing revival aligns with the desire for creativity without a correct method.

The letters themselves become artefacts of your mood and context, revealing to the recipient not just information but a little of your interior world.

Beyond nostalgia — reclaiming agency

It’s tempting to frame the letter writing revival solely as a nostalgic yearning for a slower past. Nostalgia plays a role, but the appeal goes deeper. Many participants are too young to have grown up sending letters; they’re discovering the medium for the first time.

The ritual acts as a counterbalance to platforms designed to maximise engagement and profit from your attention. Writing a letter is not just slower; it’s more deliberate. You decide when to write, what to include and who will see it. No algorithm interferes.

This sense of agency extends to how we experience time. Constant connectivity compresses time into a scrolling present. You write in one moment and deliver your message to someone else’s future. They read it days later in their own present. In between, the letter travels physically across landscapes.

There is something grounding in knowing that your words are moving through the same postal systems that once carried love letters, wartime updates and birthday cards. The letter writing connects our hyper‑modern lives to this continuum.

The social contract is different

Instant messaging has unwritten rules. Replies should be quick. Long pauses need explanations. Threads must stay alive. When you break those norms, people assume something is wrong.

Letters sidestep all of that. A letter arrives when it arrives—no typing indicator, no real‑time presence required, no fear of being buried under a feed. You open it on your terms, respond on your own timeline, and silence in between isn’t seen as neglect; it’s built into the medium.

That shift reshapes what you’re allowed to say. In a text thread, you often feel obligated to maintain contact. On paper, you can complete a thought without worrying you’re monopolising someone’s attention. You can digress, tell a story, describe a mundane detail, and the slowness removes the pressure to be witty or always “on.” You don’t need to be current; you just need to be present on the page.

Pen‑pal relationships fit perfectly into this slower lane. Everyone agrees up front: there’s no race to reply, no streak to maintain. The relationship is measured in envelopes, not pings.

Pen pals: what they are, and why they fit this moment

Earlier in this essay the term “pen pal” appeared in passing.

For readers who may not be familiar with it, a pen pal refers to someone with whom you exchange letters regularly. In the twentieth century, pen‑pal programs paired students from different regions or countries so they could practise languages and learn about each other’s lives.

Within the letter writing revival, a pen pal could be an existing friend or a stranger matched through an online service. The relationship unfolds through handwritten notes rather than instant messages, often with days or weeks between replies. That pace fosters patience and reflection.

Many Canadians now rediscover slow communication by having a pen pal (sometimes informally called an “open pal”), building a bond that isn’t mediated by algorithms. Each letter becomes a small, intentional act of connection, carrying slices of everyday life across time and space.

For a lot of people, this is the easiest way back into letter writing — or the cleanest way in, if you’ve never done it.

Quick references (if you want a place to start):

• Postcrossing (postcard exchanges)

• Meetup (search for local letter-writing groups)

And yes: some people find pen pals through Instagram or TikTok, which is a little ironic in a piece like this. But it can function like a ferry: you use the feed briefly to find someone, then you leave the platform behind.

Close

The return of letter writing isn’t a manifesto against tech. Few of us are swapping smartphones for stationery. What’s happening is: people are making space for one channel where speed and visibility don’t govern every exchange.

A letter is private in the simplest sense. It travels from one person to another and then sits on a table, waiting, rather than floating in a public feed. For adults who move through a haze of updates and alerts, there’s something almost jarring about that—communication that isn’t designed to be shared, optimised or kept on life support by constant replies. It’s just there, tangible and quietly complete.

Ane Campos.

I am a lawyer and a Digital Law specialist with over 10 years of experience in social assistance. My professional background allows me to bring a unique perspective that connects personal development, emotional resilience, and the impact of the digital world on self-esteem and clarity of purpose.